Our tenth blog of the 2016-17 class comes from Lily Kearns, who looks at a copy of first edition of James VI and I’s Workes, which is held by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons.

After the Union of Crowns in 1603, James VI of Scotland also gained the title of James I of England and Ireland. This book entitled ‘The Workes of The Most High and Mightie Prince, James’ includes some of the major literary works of King James written in the vernacular. It not only confirms his reputation as a prolific writer but also portrays James as a true Renaissance Monarch, with a keen interest in bringing glory to the English language through literature. The book contains a collection of James’ most accomplished religious and political writings. It was printed by Robert Barker and John Bill and the book was published by Bishop James Winton in 1616.

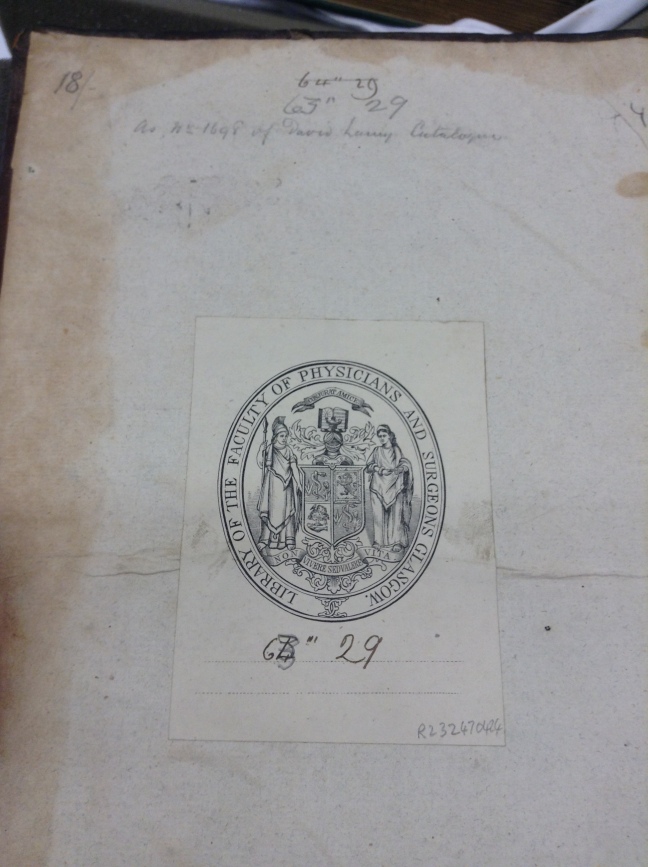

This particular copy, found in the library of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow is unique in various ways.

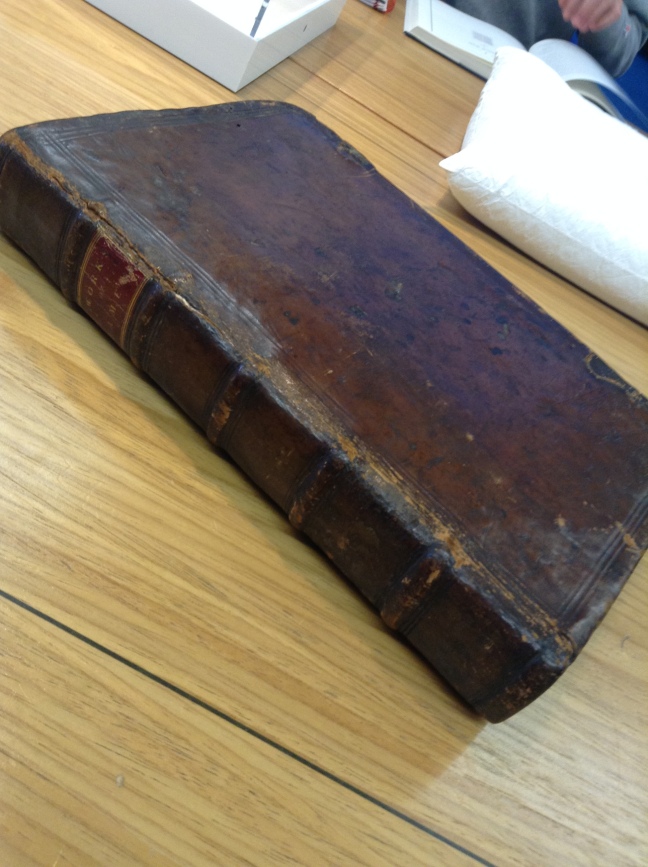

The physical book is impressive to look at. It is quite a large and heavy book measuring 13.5 inches up and 9.5 inches across. It is bound in Calfskin over wooden boards, with a simple three-line blindstamp border, blind stamp initials, and evidence of two brass clasps. The pages of the book are torn and creased with watermarks and ink stains – suggesting the book has seen a fair amount of usage over the years. One of the title pages appears to have been ripped out but the main cover page and a page displaying the Royal Coat of Arms still remain.

Some of the most intriguing physical features of his copy of the book are the inscriptions and other marginalia found throughout the book. For instance, the name, ‘Francis Hamiltoun’ has been inscribed on the dedication page and the initial F.H on the dedication page.[1] This is thought to have been Francis Hamilton of Silver-town hill, a man who spent a lot of time writing about King James and praising his work. On p.568 the name ‘Leues Kennedy’ is inscribed. Although the library staff at the Royal College have identified who they believe these men to be, there has been scarce research into the significance of these men as owners of the book. On the front and back covers of the book, the initials H.C. have been imprinted. It is still unknown who H.C. was. These different names marked on various pages of the book are significant as they are an indication that this book had multiple owners over the years and has been a useful source to many.

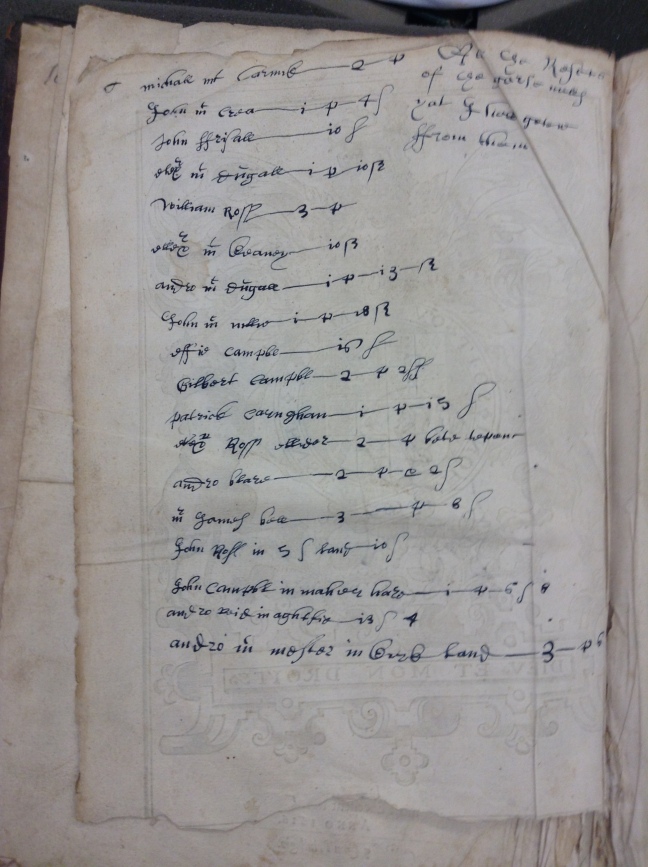

Perhaps the most interesting example of inscriptions in this of this copy of the book is a page inscribed with a list of names with sums of money indicated to be rents, written in Scottish secretary hand. Initial research points to the book possibly belonging to the one of the Earls of Galloway but this remains speculative.[2]

The most significant aspects of this book are the various inscriptions implying the varied ownership of this particular copy and the fact that it is held in the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons among medical books and journals while being non-medical in content.

It is important to recognize the significance of this copy of the works of King James being held in the library of the royal college of surgeons and physicians. This perhaps has a lot to do with the personal relationship between Peter Lowe and James VI and King James’ involvement in the foundation of the college. In 1599 King James granted the founding charter of the faculty of physicians and surgeons of Glasgow.[3] Lowe had received extensive humanist education on the continent in medicine and when he returned in 1598 he was unimpressed with the way the practice of surgery in particular was being approached in Glasgow.[4] Although James knew little about medicine himself, he took an interest in it and it is largely thanks to him that the teaching of medical practice in Glasgow and the West was able to change under the influence of Lowe. [5] This book is perhaps a testimony to James’ reputation as a Renaissance King. It is part of the general collection at the Royal College. This is not the only copy of the book but there is little known about the whereabouts of other copies by those at the college.

It is not unreasonable to speculate that King James and Peter Lowe had a more personal relationship than it might seem and even a friendship. Perhaps this is why King James was so quick to endorse the College. It is recorded that Lowe had at some point served as a personal Physician to James’ son and so it is not unlikely that he would have developed some kind of friendship with the Royal Family prior to the charter being granted. He seems to have been held in high esteem by the King who refers to him as ‘our chirurgiane and chirurgiane to our dearest son the Prince.’[6]

The fact that this book found in the College is testimony to the importance of the founding charter, issued by King James, in the formation of the College and paints James as a King that followed Renaissance principles and humanist ideas surrounding the study of medicine endorsed by Lowe. An original portrait of King James hangs in the main hall Royal College today.

The Renaissance was a period that welcomed vast amounts of literature of all kinds and James Stewart, born in 1566 at the height of Scottish Renaissance culture, is thought have began writing as early as the age of fifteen.[7] Although this particular collection of the works of James shows some of his impressive political and ecclesiastical writings, it does omit much of the poetry written by the King. By the age of 18 James had already released a book containing his poetry, The Essays of a Prentise, in the Divine Art of Poesie.[8] It is clear that James regarded poetry and literature as extremely important. This is one way in which he lives up to his reputation as a patron of the humanist principles and a model of Renaissance Kingship. However, his poetry was not just of personal significance. Peter C. Herman has noted that ‘no monarch before James had their verses printed in a book for circulation as a commodity in the market-place’.[9] He continued to write throughout his teenage years and as he grew older his works became more prolific and widely known. In fact more governmental and administrative documents survive for his reign than for that of Elizabeth.[10] While James is well-known among scholars today as the King who commissioned the Authorized (King James) Version of the holy bible and glorified the English Language, many people are unaware of James’ intellectual and scholarly works.[11] This book containing some of the most impressive of James’ works shows his engagement in religious and political issues and discourse. The most notable works included in this volume are his writings on ‘deamonologie’ regarding witchcraft, his scriptural interpretations of the Old Testament, his Political Works on Kingship as a God given Right and his various speeches to Parliament. All of these works have been written in the vernacular, which is significant in showing James as a patron of Renaissance Literature.

The book was printed in 1616 by Robert Barker and John Bill who made up part of the King’s Printing House (KPH) and were engaged with the trade of books overseas and within the Kingdom.[12] It was through the KPH that the works of James were able to circulate and be read and studied by so many. The various inscriptions and different initials and names found throughout this book are evidence that this copy was passed around and regularly used.

This particular copy, containing of the works of King James, was edited by James Bishop of Winton formerly known as James Montagu. Winton was a graduate of Christ’s College, Cambridge, and in 1596 he became the first Master of Sidney Sussex College, for which he laid the foundation stone.[13] Montagu not only headed a college as a young man, but he also became a very important figure in the life of King James, serving as his personal Chaplain and dean of his Chapel. He was very attentive to the spiritual needs of the King and his family. It is said that no Clergyman had as close a relationship with James than Montagu. His familiarity with King James led to him being appointed to higher positions within the Church, however Montagu insisting on remaining in the King’s household. His devotion and service to the King was impressive.[14] It is significant that James employed and befriended such enlightened and intelligent people. This is further evidence of his Renaissance style Kingship.

It is thought that this particular copy of the book was owned by one of the Earls of Galloway. This conclusion has been drawn as a result of the inscriptions made on the verso of the page baring the Royal Coat of Arms. It is written in Scottish Secretary hand which is a type of writing characteristically used in the 16th and 17th Century.[15] There is a list of 18 names next to which are sums of money indicated to be rents. Four place names can also be found which have indicated the origins of this writing to be from Wigtonshire and has lead to the conclusions about the Earl of Galloway.[16] It is significant that the book was owned by such a group of noblemen. However it is intriguing not only that this book may have been owned by the Earl of Galloway but that such a significant and expensive book would be used for scribbling and note taking. Makes sense that it could become property of the Earls of Galloway. They are distant relatives of the Stewart King.

To conclude, the book itself is important in showing James’ significant literary contributions and his reputation as a man of intellect and a Renaissance King. This particular copy of the book is unique and has special significance in many ways. Namely, it’s location in the Royal College and the various inscriptions throughout the book indicating that it has had different owners over the years and has been widely read.

How could we make this book more available to the public?

This book is extremely significant in showing the extensive literature produced by King James VI and I, but it is also important in showing his engagement in the ideals of the Renaissance in Scotland. Although James is remembered today as an important Monarch, often one can be guilty of forgetting why this is. James VI’s significance is sometimes lost amongst that of the long line of other Stewart King’s. Often history focuses on James’ role as the head of the reformed Kirk and in the Church in England but there is so much more to his story. It would be beneficial for the general public to discover James as a writer, a political thinker, and a man of great intellect. A King interested in humanism and most importantly as a Monarch of the Renaissance.

One way in which this particular copy of the book could be showcased and made more widely available to the public would be to incorporate it into a historical display to the theme of the Stewart dynasty or important figure in the Renaissance. Perhaps having the book displayed amongst other important texts of the Renaissance or other Stewart artefacts in a display at Linlithgow Palace would be an effective way of bringing attention to this copy. Linlithgow Palace is extremely significant in the story of the Stewarts. It is regularly visited by the public and by groups of school children for education purposes. A display of this kind could be an excellent way of promoting James’ work.

[1]James j Beaton, Roy Millar, Iain t Boyle, Treasures of the college, (Edinburgh: 1926) p. 69

[2] Treasures of the College, ibid, p. 69

[3] IML Donaldson, Peter Lowe’s Whole Course of Chirurgerie, 1597, (2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh) p.374

[4] Donaldson, ibid

[5] Treasures of the college, ibid, p.16

[6] Treasures of the college, ibid p.69

[7] Jane Rickard, Authorship and Authority: The Writings of James VI and I, (Manchester University Press:1824) p.1

[8] Rickard, ibid, Authorship and Authorit, p.33

[9] Rickard, ibid, p.33

[10] Pauline Croft, King James, (Palgrave Macmillan: 2003) p.1

[11] Croft, King James, ibid, p.37

[12] Author unknown. A Brief History of the King’s Printing House (KPH) in the Jacobean Period, <http://www.english.qmul.ac.uk/kingsprinter/publications/transcripts/Reader_Aids/A_Brief_History_of_the_Kings_Printing_House.pdf>

[13] Croft, King James, ibid, p.93

[14] Kenneth R Mays, Richard Lambert, King James Bible Translators: James Montagu, (2016) <http://kingjamesbibletranslators.org/bios/James_Montagu>

[15] Treasures of the college, ibid, p.69

[16] Treasures of the college ibid. P.69

Reblogged this on ruthfletcherhunterian.

LikeLike

Why can not copies of this be made available to the public….so much in the recent years has been so negative about King James that we need some truth ……

LikeLike